A few weeks ago I gave a talk at the Houston Church of Freethought. The subject was on "Freethought and Compassion". Finally, I have gotten around to editing the presentation into a presentable essay in print, formatting it, and noting references. If anyone would like to read it, it can be found on my philosophy site, or by clicking HERE.

A few weeks ago I gave a talk at the Houston Church of Freethought. The subject was on "Freethought and Compassion". Finally, I have gotten around to editing the presentation into a presentable essay in print, formatting it, and noting references. If anyone would like to read it, it can be found on my philosophy site, or by clicking HERE.

Blog Site

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Presentation on Compassion

A few weeks ago I gave a talk at the Houston Church of Freethought. The subject was on "Freethought and Compassion". Finally, I have gotten around to editing the presentation into a presentable essay in print, formatting it, and noting references. If anyone would like to read it, it can be found on my philosophy site, or by clicking HERE.

A few weeks ago I gave a talk at the Houston Church of Freethought. The subject was on "Freethought and Compassion". Finally, I have gotten around to editing the presentation into a presentable essay in print, formatting it, and noting references. If anyone would like to read it, it can be found on my philosophy site, or by clicking HERE.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Evil and Ignorance

Socrates is written to have said, "There is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance."[1] Generally, he was saying that people do not do evil, except by ignorance. This statement sounds very simple, and many people think they understand it when they read it; but in my view, they don't.

Socrates is written to have said, "There is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance."[1] Generally, he was saying that people do not do evil, except by ignorance. This statement sounds very simple, and many people think they understand it when they read it; but in my view, they don't.It seemed to me Socrates was saying that even the worst, most treacherous villains wouldn't be so if they were only more knowledgeable of their deeds. But surely, not all people are simply 'doing the best they can', and are simply misguided or mislead. Many people do indeed confuse right and wrong, but some people know an act is wrong even as they are doing it. As proof of this, they may even feel guilty or ashamed as they do it.

Therefore, when I first read this statement of Socrates, I thought it terribly naive. I was wrong. I wasn't wrong about people; some people do knowingly have malicious intent. But I was wrong about what Socrates was saying. I think many people today are wrong about this, and proceed as though there is no such thing as evil people; as if we're all just 'doing the best we can'. Because they share my once-shallow interpretation of Socrates' words, they mistakenly think he backs up this naive view.

The truth in what Socrates is saying here is not so important because of what it says about people, however. Rather, what he says is important because of the profound thing it says about goodness and virtue.

People who do evil are ignorant. But the common mistake in interpreting this notion is to misunderstand what it is they are ignorant of. Evil-doers with intentionally malicious aims are not ignorant of what is good and what is evil - on this, they are clear, even if they may be unwilling to admit it to themselves.

Instead, what these sorts of evil-doers are ignorant of is the fact that virtue and wisdom are one and the same. They look at virtue as a sort of external set of rules applied on top of life, sometimes limiting our choices and not allowing us to do what is necessary or beneficial to us. These sorts of people tend to be good because of social pressures, or seeking rewards, or fear of punishments, or emotional urges. They will, when they think it to their advantage, do what they know to be evil.

The mistake they make is in their perception of what virtue is. What they don't understand is that virtue is always the wise course of action, and the wise course of action is always the virtuous one. There is never a time when the practical, pragmatic, necessary, efficient, or beneficial thing to do is non-virtuous. If they think so, it is because they're not considering all of the relevant variables in the long term. Their definition of "practical", "efficient", or "beneficial" may be short-sighted.

In summary, intentional evil-doers are ignorant of the fact that virtue and wisdom are synonymous. They are also ignorant of the fact that virtue is both necessary and sufficient for living a truly happy life.

This may be a difficult truth to grasp at first, and may even seem counter-intuitive to some. It's a certain conceptual understanding of how events flow together and how lives and true happiness are affected by different things. Indeed, finally 'getting it' on a deep level is a lot like that moment when your eyes settle into the right configuration to see the 3D picture in a stereogram. But as long as this form of ignorance remains, the person will be retarded in their ethical development to the level of child, and their well-being will suffer as a result.

[1] Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

The Minions of Hitler

Buddha taught the interdependence of all things and dependent origination (the doctrine of "Pratitya-samutpada"). This basically means that all things exist because of pre-existing conditions and cause and effect. This could be considered a statement of physics, long before the school of physics had so distinctively branched into its own from philosophy. It may seem an obvious observation to us today, but in a time and place where people commonly suspected things to happen because of luck, the gods, magic, and so on, the notion of cause and effect would have been an important milestone in human reasoning and understanding.

Buddha taught the interdependence of all things and dependent origination (the doctrine of "Pratitya-samutpada"). This basically means that all things exist because of pre-existing conditions and cause and effect. This could be considered a statement of physics, long before the school of physics had so distinctively branched into its own from philosophy. It may seem an obvious observation to us today, but in a time and place where people commonly suspected things to happen because of luck, the gods, magic, and so on, the notion of cause and effect would have been an important milestone in human reasoning and understanding.Something occurred to me recently, in thinking about all of the world's current troubles with terrorism, war, the Iran situation, the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians and so on.

All of this leads back to Hitler in one way or another. The formation of Israel was endorsed by other nations largely because of sentiment resulting from the holocaust. Many of the political borders and situations in the middle east region came about because of British decisions and promises resulting from World War II. Our relationship with Russia comes after a long cold war, made possible by nuclear weapons developed during the war. Russia is still a source of concern in that many of its nuclear assets may be in questionable hands, not to mention many political complications that still exist in our efforts to fight the war on terror.

Of course, true understanding of dependent origination would mean that we would also know Hitler (and his power given him by the people of Germany) was a result of other causes, such as an economically oppressed pre-war Germany. There is no "end point" we can solidly blame for everything. Another fact of dependent origination would be that causes are rarely singular. More often, they are part of an intricate web of complex causes. It wasn't "just" Hitler's choices, but many other converging causes coming into play that brings us our current problems (including, of course, more recent decisions by our own governments).

But, certainly, there are major causal "hubs" in this tapestry; high points of causation where events take a major shift. Hitler would seem to have caused a significant turning point in global events, and is major "hub of causation".

So, all over the world, we are still being slaughtered by Hitler from beyond the grave to this day. In many respects, all of our current efforts to find peace or what we think is justice in the world, be we Americans, Russians, Palestinians, Israelis, Iraqis, or Iranians, are efforts to escape Hitler's karma.

If this is true, then it is clear why we have been unable to do so. Hitler, in this sense, was not merely a human being who lived in a certain time. Hitler created the karma he did because of who he was, his proclivities, tendencies, and his responses to his world. These responses included a lust for power, racial hatred & supremacy, barbarism, manipulation of mass sentiment through power of the state, global hegemony, and more.

The reason we cannot escape Hitler's karma is that we have been attempting to do so by using his means, to one degree or another. In this manner, we keep the essence of Hitler alive and are all, every nation on all sides, to some degree still minions of Hitler, carrying out his will.

It seems to me, the only way to escape Hitler's influence, is to utilize other responses. I have stated before that one who fights fire with fire will end up with a burned home. We must find responses that counteract the karma of Hitler if we are to ever escape them.

This, of course, boils down to what we all know. The real problem before us is that these things are easier said than done. I still don't have a satisfactory answer, but I'm convinced that the key (our "foot in the door" so to speak) is that all beings crave justice and happiness. If we start with that, then we should be able to figure something out.

Just some random thoughts.

Friday, April 14, 2006

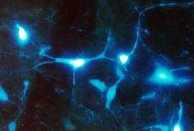

Revulsion at the Natural Brain

There have long been debates about whether our minds are the products of brain activity, whether our brain activity is our mind, or whether something else (natural or supernatural) is responsible for our consciousness and sensations.

There have long been debates about whether our minds are the products of brain activity, whether our brain activity is our mind, or whether something else (natural or supernatural) is responsible for our consciousness and sensations.Those who have suffered brain damage have experienced changes and losses in some aspects of their consciousness[1]. Some have shown drastic changes in personality. Memories, thoughts, opinions, and consciousness have all been seen to change, and change in direct relationship to the area of the brain one would expect given the behavior[2]. Even external stimulation of regions of the brain result in experiences of thoughts, memories, emotions, and feelings[3]. In every case, it seems to be exactly what one would expect if the mind, our thoughts, and our consciousness, were fully a result of the physical activity in the brain.

What we experience subjectively may simply be "what it feels like" to be a biochemical information processor. When we experience thoughts of a tree for example, that's what it feels like to be an informational system whose neurons which code for trees are active.

Is this necessarily true? It seems to me to be a very likely straightforward possibility, without assuming additional phenomena which are yet to be proved. While it's possible there may be all sorts of other invisible/magical/paranormal/other-dimensional/unknown/whatever phenomena going on, it seems to me the only reason to particularly believe this is out of an emotional urge to want to believe otherwise.

This urge is related to the fact that when a lot of people think about the possibility of being a fully material biochemical information processor, they think of it as degrading, or meaningless, or bland, or even horrific.

But this is merely a socially learned response. A response learned from a society which, somewhere along the line, tragically split its conception of reality into the material and a non-material realm. Like a suicidal village dumping all of its food for the winter into the river, we proceeded to conceptually deposit everything and anything meaningful, beautiful, or dignified into this unseen and unknowable realm.

The result, centuries later, is a society which engenders in its people, from the time of youth, a base-level, almost primal, feeling that anything material is ultimately worthless - and this notion lingers, even in the back of the minds of those who have consciously rejected the supernatural. In its place these folks sometimes create paranormal and "as yet unknown" natural realms - basically modern day stand-ins for the supernatural which are perceived to be more intellectually respectable than talking about magic.

But some see nothing undignified or meaningless or horrible in our material universe. In fact, they find it quite wondrous, beautiful, and awe-inspiring. The fact that we can experience the consciousness and qualia we do in such a universe is all the more cause for awe. For these folks, there seems to be no reason for a negative reaction to the idea of exclusive naturalism. And were it not for such a reaction, the above understanding of the mind as physical/informational function would be the obvious conclusion of nearly anyone (until or unless some provable indicators to the contrary popped up in research).

It's also puzzling to me just what would avoid a similar negative reaction. Imagine if we were to ever discover for certain a non-physical phenomenon that transcended or operated in addition to physical brain function. Later, we might begin to discover specifics about how it operated, of what it was composed, and so on. Before long school children would be nodding off to 'boring' lectures on the ‘laws of the non-physical’.

It seems to me in this case, the same people who weren't satisfied with material explanations would also not be satisfied with this, and begin to find these datum to be similarly horrible and meaningless.

Refusing to settle for anything but the mysterious, they would then have to imagine and postulate *further* explanations beyond what had been discovered. You can bet that all of these extra notions would be logically self consistent, fully possible, and would be impossible to ever disprove (such scenarios are easy to construct).

All of this, because of a peculiar connection in their minds between the unknown or mysterious and the beautiful or meaningful - a somewhat egotistical necessity, being "only that which is unknowable is suitable to explain myself".

I can't comprehend or relate to such a necessity, for either intellectual or even aesthetic reasons.

[1] Morten L. Kringelbach, "Emotion, Learning and Reading"

[2] The Franklin Institute Online, "The Human Brain"

[3] Spirituality and the Brain, "The Sensed Presence and Vectorial Hemisphericity"

Monday, April 10, 2006

Denver on Nature & Life

Recently I've listened to some John Denver songs, which I've heard many times before, but not for a long time. Of course, Denver's love of Nature was well known. For someone who has been exploring ancient conceptions of the 'divine' and profound in Nature, before later notions of duality, separation, and "supernaturalism" came along, Denver's songs take on new meaning than they did when I heard them years ago. Some favorite passages include:

Recently I've listened to some John Denver songs, which I've heard many times before, but not for a long time. Of course, Denver's love of Nature was well known. For someone who has been exploring ancient conceptions of the 'divine' and profound in Nature, before later notions of duality, separation, and "supernaturalism" came along, Denver's songs take on new meaning than they did when I heard them years ago. Some favorite passages include:"You fill up my senses like a night in the forest, like the mountains in spring time, like a walk in the rain, like a storm in the desert, like a sleepy blue ocean..."[1]

The power of the music in this passage invigorate the lyrics and give the listener a sense of the power and majesty Denver experiences in Nature. In the next line, one gets the sense of the profound beauty inherent in the fact that life on this planet is ancient.

"Almost heaven, West Virginia... Life is old there; older than the trees, younger than the mountains blowing like a breeze."[2]

Through a character that is 'born again' upon visiting the country, Denver says of the sky,

"I've seen it raining fire in the sky. The shadows from the starlight are softer than a lullaby."[3]

But for Denver, it seems Nature doesn't stop with the country. His zeal for Nature is one with, and inseperable from, his experiences of life and love; in things as simple as the sting of moonshine and sounds on his radio. He expresses humanistic values when he uplifts the unique treasure that others might disregard as a drunkard in a prison cell in his rendition of Mr. Bojangles. To his wife he asks,

"Come let me love you. Let me give my life to you. Let me drown in your laughter. Let me die in your arms..."[1]

John Denver said, "The purpose in my music has always been to communicate the joy that I find in living." To those of us who find Nature quite "super" enough as is, John Denver's music serves as hymn.

[1] Annie's Song

[2] Take Me Home, Country Roads

[3] Rocky Mountain High

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)